Editor's Picks

Plant Focus

This Species Spotlight article is in two parts: the first section, by Parisa Panahi and Mehdi Pourhashemi, examines Quercus castaneifolia in habitat in Iran; the second section, by John Anderson, is an account of the species in cultivation in the rest of the world.

Parisa Panahi1 and Mehdi Pourhashemi2

1 National Botanical Garden of Iran, Botany Research Division, Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran, Iran

2 Forest Research Division, Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran, Iran

Geographical distribution

Quercus castaneifolia C. A. Mey. (chestnut-leaved oak) is distributed in the Caucasus (Azerbaijan, in the Talysh region located along the southwestern shores of the Caspian Sea) and throughout the Hyrcanian forests of Iran. It is the dominant species in pure and mixed stands covering about 6.5% of the Hyrcanian forests (Anonymous 2003). The best stands of this species can be observed in eastern areas of the Hyrcanian forests (Golestan province) (Fig. 1).

©Majid Hasani

It can be found on the lowland plateau, together with other broad-leaved trees, in particular with Buxus hyrcana, and up to 1000 m.a.s.l., where it is mixed with Carpinus betulus. The upper distribution limit of this species depends on geomorphology, climate and soil, but individuals of this species can be found to an altitude of 2400 m.a.s.l. At higher altitudes it prefers warm and sunny slopes (Gorgi Bahri 1988).

This species forms two distinct communities in the plain areas of Hyrcanian forests as follows (Mobayen & Tregubov 1970):

- Querco-Buxetum: Growing on permeable sandy soils, this is a plant community exclusive to the Caspian coastal plains. Two distinct strata are found in this community. The first stratum consists of Q. castaneifolia trees along with species like Acer velutinum, Alnus glutinosa, and Pterocarya fraxinifolia. The second stratum is very dense, consisting of Buxus hyrcana, Gleditsia caspica, Albizia julibrissin, and Diospyros lotus, as well as a ground cover of ferns, e.g. Pteris cretica, and grasses, and a number of moss species growing on the ground and hanging from tree branches, providing eye-catching scenic effects in these forests (Fig. 2).

© Khosro Sagheb Talebi

- Querco-Carpinetum: This is found in the lowlands on northern slopes in Gilan and Mazandaran provinces, which have a lower relative humidity than the sites of the former community. Quercus castaneifolia makes up usually two-layered stands, with oak in the upper storey and Carpinus betulus in the lower storey (Figs. 3 and 4).

© Habib Zare

© Khosro Sagheb Talebi

Towards the drier climate to the northeast, the community gradually transforms into a Zelkovo-Quercetum community. In upper communities (especially Parrotio-Carpinetum and Fagetum hyrcanum), it found as individuals or small groups (Figs. 5 and 6).

© Majid Hasani

© Mehdi Pourhashemi

Quercus castaneifolia has a high longevity, and some old individuals with huge dimensions (more than 3 m DBH and 50 m tall, and 500 years old) can still be found in Hyrcanian forests (Sagheb Talebi et al. 2014; Figs. 7 and 8).

© Mostafa Khoshnevis

Since the habitats of oak are mild with less steep slopes and also have easy access, the oak stands have been harvested for centuries. The proportion of oak is hence lower than before, and the stand volume and natural regeneration ability has decreased dramatically (Marvie-Mohadjer 1983).

© Mostafa Khoshnevis

Ecological demands

Quercus castaneifolia is a light-demanding species. In areas with sufficient light, it produces an expanded crown. The soil of Q. castaneifolia habitats at lower elevations is usually semi-deep calcareous brown with a moderate texture and a pH between 5.8 and 6.8, whereas at middle elevations it is a deep clay loam to clay, forest brown soil with a pH between 5.3 and 6.2. At higher altitudes, rendzina soils (pH=7.3), and in flat habitats, hydromorphous soils (pH=5.1) are also reported for oak stands (Habibi 1983; Gorgi Bahri 1988).

© Parisa Panahi

Due to the beautiful form of the tree, it is planted in urban green spaces and botanical gardens in Iran (Figs. 9 and 10).

© Parisa Panahi

Taxonomy

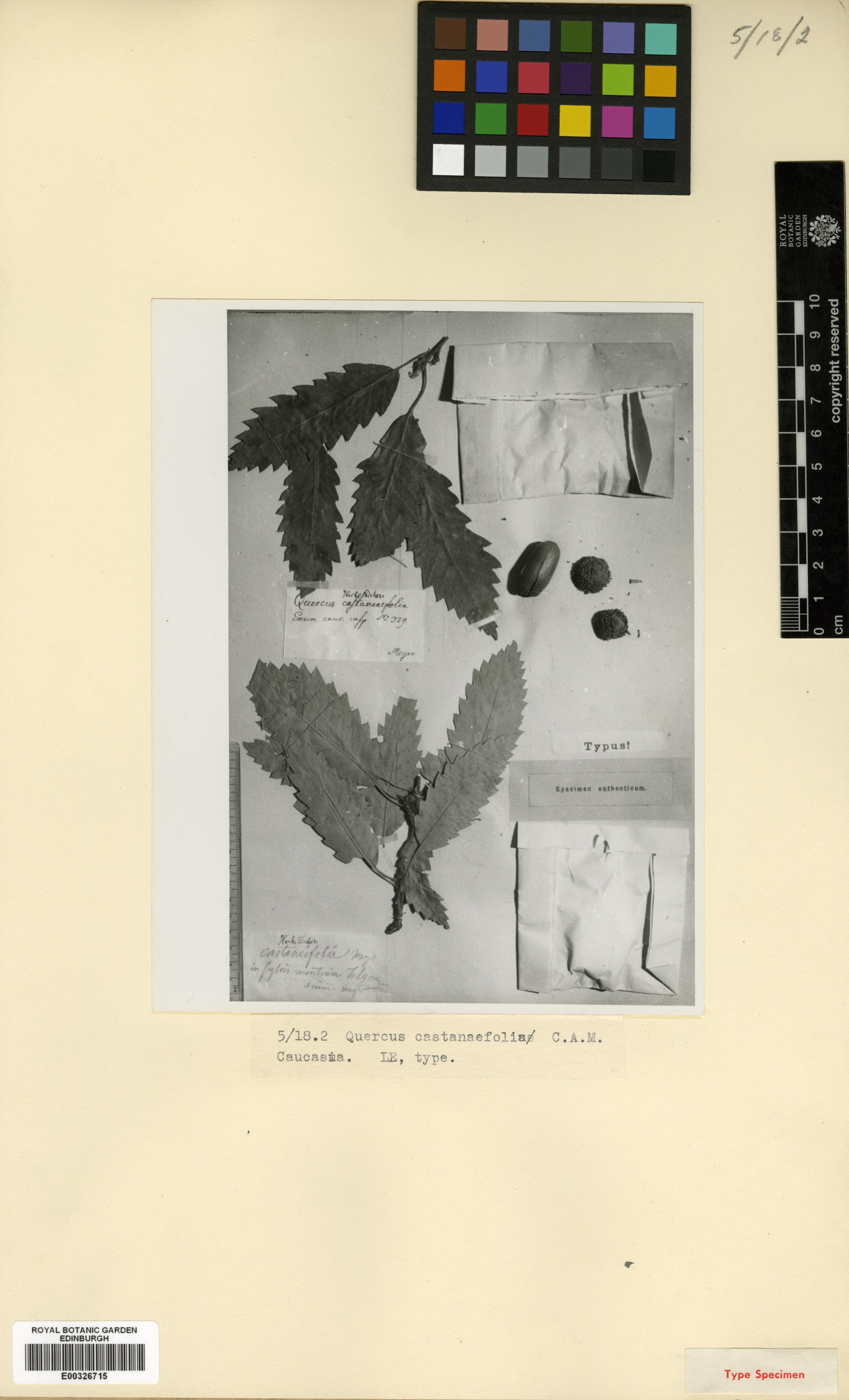

Quercus castaneifolia shows morphological variations in leaves and acorns characteristics. Panahi et al. (2011) noted that the delimitation of species, subspecies, and varieties varies according to different authors. Quercus castaneifolia was described in 1831 by Carl Anton Meyer (1795-1855) from the Caucasus and Hyrcanian forests of Iran (Fig. 11).

In 1935, Otto Schwarz examined three oak samples from Iran; one of them, from Bandar-e Gaz forests in Astarabad province (current name: Golestan province), was collected by Paul Sintenis (Iter Transcaspico-persicum no: 1383, 1900-1901). The other two, from Gilan province (Rasht region), were collected by Bornmüller (Iter persicum alterum, no: 8247-8248, 1902). These three samples were named Q. sintenisiana by Schwarz, based on trichome characteristics :

- Quercus sintenisiana O.Schwarz in Notizbl. Bot. Gart. Berlin-Dahlem 12: 468 (1935)

Aimée Antoinette Camus (1879-1965), in her monograph of world's oaks, reported two subspecies for Q. castaneifolia; subsp. eucastaneifolia A. Camus and subsp. aitchisoniana A. Camus from Hyrcanian forests:

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. eucastaneifolia A.Camus, Chênes, Texte 1: 552 (1938)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. aitchisoniana A.Camus, Chênes, Atlas 1: 45 (1934)

Alphonse de Candolle (1864) introduced a new variety of this species, described as having glabrous leaves:

- Quercus castaneifolia var. glabriuscula A.DC. in A.P.de Candolle, Prodr. 16(2): 50 (1864)

This variety is accepted by Camus (1936-1938) and Sabeti (1966). Freyn (1902) also described a form of this species based on the leaf lobes:

- Quercus castaneifolia var. obtusiloba Freyn in Bull. Herb. Boissier, sér. 2, 2: 904 (1902)

Camus also wrote that Q. castaneifolia var. obtusiloba Freyn presents leaves with deeper sinuses at the base and generally smaller, more papery-like leaves, with obtuse rather than acute teeth. She also notes that a range of intermediate forms exists and that this particular one seems to be characteristic of lowland forests.

The most complete study of Quercus in Iran was done by Djavanchir Khoie (1967), using leaf and acorn morphology. Based on leaf venation, he classified oaks of Iran into two subgenera: Quercus (with lobed leaves) and Complanate Djav.-Khoie (with dentate leaves). Based on the number of stamens, the subgenus Complanate was divided into two sections: Oligandrae Djav.-Khoie and Polyandrae Djav.-Khoie. According to this classification, Q. castaneifolia belongs to section Oligandrae. He treated Q. sintenisiana and Q. castaneifolia subsp. eucastaneifolia as synonyms of the type species and accepted Q. castaneifolia subsp. aitchisoniana as a separate taxon. He introduced six new taxa as follows:

- Quercus castaneifolia var. ellipsoidalis Djav.-Khoie in Chênes Iran: 68 (1967)

-Quercus castaneifolia var. minuta Djav.-Khoie in Chênes Iran: 69 (1967)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. incurvata Djav.-Khoie in Chênes Iran: 72 (1967)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. subrotundata Djav.-Khoie in Chênes Iran: 73 (1967)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. triangularis Djav.-Khoie in Chênes Iran: 75 (1967)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. undulata Djav.-Khoie in Chênes Iran: 77 (1967)

Among the various taxa of this species, subsp. undulata (Fig. 12) is very similar to Q. cerris in its cupules,,although it differs in the basal scales, which are broad and curved. It is possible that subsp. undulata shows the transition from Q. castaneifolia to Q. cerris. It seems that molecular studies could help determine the correct differentiation.

On the other hand, there are similarities between Q. castaneifolia and Q. afares Pomel. The morphological characteristics are almost the same, which is why some botanists have accepted their identity (Mathieu 1877). Similarly, Bean (1914) considered Q. afares a variety of Q. castaneifolia, which he described as var. algeriensis. According to R. Maire (1961), Q. afares is a subspecies of Q. castaneifolia and very close to Q. cerris.

- Quercus castaneifolia var. algeriensis Bean in Trees & Shrubs Brit. Isles 2: 304 (1914)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. afares (Pomel) Maire in Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Afrique N. 24: 227 (1933)

Menitsky, in Flora Iranica (1971), placed Iran’s native oaks in subgenus Quercus and in two sections: Quercus and Cerris. In this classification, Q. castaneifolia was considered to be in section Cerris, subsect. Cerris and all infraspecific taxa recognized by Djavanchir-Khoie and Camus were treated as its synonyms. He recognized only Q. castaneifolia C. A. Mey. subsp. castaneifolia from the Hyrcanian forests of Iran.

Sabeti (1994) noted that the differences between subspecies and varieties of Q. castaneifolia are due to heterophylly (i.e., variations in leaf shape on the same plant), but according to Djavanchir-Khoie (1967), the acorn shape and tree form are the basic characteristics for differentiating the subspecies and varieties of Q. castaneifolia in the north of Iran.

Panahi, in her PhD thesis (2011), surveyed the habitats of Q. castaneifolia and studied their distribution, populations, and ecological conditions. She focused on the micro-morphological characteristics of leaves and pollen grains to evaluate the taxonomic significance of these characteristics for the identification of the taxa introduced by Djavanchir-Khoie. She confirmed four infraspecific taxa: Q. castaneifolia var. castaneifolia, Q. castaneifolia var. minuta, Q. castaneifolia subsp. aitchisoniana, Q. castaneifolia subsp. undulata. Also, she introduced a new subsp. recurvatus.

- Quercus castaneifolia var. minuta Djav.-Khoie in Turkish J. Bot. 42: 670 (2018)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. undulata Djav.-Khoie in Turkish J. Bot. 42: 670 (2018)

- Quercus castaneifolia subsp. recurvatus H.Zare & Panahi in Acta Bot. Hung. 65: 124 (2023)

Some micromorphological characters of leaf and pollen grain, such as type of trichome, number of trichome rays, and ornamental features of pollen, have proved to be diagnostic for infraspecific classification of Q. castaneifolia in the Hyrcanian forests of Iran.

Botanical description

Deciduous slender large tree, reaching 40–50 m in height, trunk 3–3.5 m in diameter, with expanded crown. Thick bark, smooth for a long time, grayish-brown in color (Fig. 13), then fissured into small scales of dark gray or black-gray color, hence its common name in Persian: black oak (Siah-mazoo). Young branches are gray and densely pubescent; one-year-old branches are almost glabrous. Two-year-old branches are hairless or almost so. Buds are almost glabrous and have linear and very elongated scales. Male inflorescence large (catkins 35–100 mm long) and slightly elongated and those of the female inflorescence almost conical (short catkins bearing 1–3 sessile flowers or on a very short, thick peduncle). Number of stamens 3–6 (often 4, rarely 6). Leaves in the bud are heavily tomentose. Adult leaves have a densely tomentose lower surface. Leaves long elliptical, oblong, or elongated. Late deciduous: some leaves remain on the tree in a dry state towards mid- or late winter. Teeth obtuse, 7–15 (often 11). Upper surface dark green, lower surface grayish-white. Stipules, late deciduous. The most frequent trichomes on lower surface sessile-stellate and multiradiate, with 4–18 (often 8–14) rays measuring 80–180 μm. Inner rays of multiradiate trichomes usually erect and the outer ones more or less horizontal, usually flattened onto the lamina (Fig. 14). Hemispherical cups with recurved scales. The cupule scales tough, tomentose, and gray on the inner side. Scale length gradually increases up to 6 mm in the base of cupule (Fig. 15).

© Parisa Panahi

© Parisa Panahi

Acorn production

So far, limited research has been conducted on the acorn production of Q. castaneifolia in Iranian forests. In a study in three areas (compartment no. 262 of the Loveh Forestry Plan in Galikesh county, Golestan province, in 2009, the forests adjacent to Loveh village in 2011, and the Tavir Forestry Plan in Fazelabad county, Golestan province, in 2011), the acorn production of Q. castaneifolia was estimated. In each area, forty sample trees were selected according to stratified random sampling. The range of DBH and crown area (CA) of sample trees were 25–168 cm and 50–491 m2, respectively. For each tree, acorn density (acorns number/m2 crown area) was estimated using acorn traps. Acorns were counted every two weeks from early September until all acorns had fallen (typically early December). The mean of acorn density was estimated to be 2.1 in compartment no. 262 of Loveh Forestry Plan, 23.3 in the forests adjacent to Loveh village, and 22.7 in Tavir Forestry Plan. The mean number of acorns per tree were 378, 4,549, and 4,364, respectively. In the Loveh Forestry Plan in 2009, while some individuals did not produce any acorns at all, some sample trees produced more than 1,500 acorns. Of course, 2009 was a year of poor acorn production for oak trees in this area. In the forests adjacent to Loveh village, the lowest acorn production of trees in 2011 was 1,100, while some individuals produced more than 8,000 acorns. In the forests of Tavir, some sample trees produced less than 100 acorns in 2011, but some trees produced more than 10,000 seeds. Overall, it was found that in 2011, the conditions for acorn production of Q. castaneifolia were much more favorable than in 2009 (Karimidoust et al. 2012).

© Parisa Panahi

Furthermore, acorn production of 30 trees of Q. castaneifolia (the range of DBH and CA were 25–50 cm and 21–127 m2, respectively) cultivated in the Hyrcanian collection of the National Botanical Garden of Iran, was repeatedly assessed between 2009 and 2011. Based on the results, the mean of acorn density was estimated 80, 23, and 68 in 2009, 2010, and 2011, respectively. The mean numbers of acorns per tree were 4,807, 1,377 and 4,144 during study years, respectively. These results indicate that acorn production of sample trees was less favorable in 2010 than in the other two study years (Panahi and Pourhashemi 2013; Fig. 15).

Quercus castaneifolia in cultivation

John Anderson

Keeper of the Gardens, Windsor Great Park, UK

The first recorded planting of Quercus castaneifolia C. A. Mey in the United Kingdom was in 1843 at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. It was introduced as an acorn, and once established as a young tree it was planted out behind the Water Lily House at Kew in 1846, probably by Sir William Hooker, the first director of Kew (Rix & Kirkham 2009). Today, it is one of the most imposing and impressive trees in the collection. It has endured and survived many great storms and droughts. In height, it has reached 36.6 m, with a canopy spread of over 30 metres and an impressive girth of 7.9 m recorded in 2017. There are two other specimens at Kew planted on the Museum Lawn from a later introduction in the early 1950s, and two more from a reintroduction by Hans Fliegner and John Simmons in 1977 from the Alborz (Elburz) mountains of Iran (Avis-Riordan 2020; The Tree Register 2025).

Since the early 1970s there have been several plant expeditions to the regions where Q. castaneifolia can be found. The most notable was in 1972 by Ann Ala and Roy Lancaster in northern Iran under the collection code (Ala & Lancaster 25). Of the three plants from this collection planted at Sir Harold Hillier Gardens, Hampshire, UK, the largest was 27.6 m × 97 cm in 2023. A specimen probably from this collection also grows at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, where it had reached 20.5 m × 79 cm in 2021 (The Tree Register 2025). Due to the unusually deep lobing on the leaves of this collection, it was originally suggested it might be a hybrid with Q. macranthera, but this is improbable as the species are in different sections, Q. castaneifolia in section Cerris and Q. macranthera in section Quercus.

© Roderick Cameron

There are several notable Q. castaneifolia, hybrids, and selected clones in various collections and parks across the UK and Ireland. At Windsor Great Park, England, two trees of the “King George VI Coronation Plantation” (representing Australia and New Zealand) were planted in 1937 as Q. castaneifolia but over time identified as Q. castaneifolia × cerris. In 2010, they measured 28 m × 100 cm and 23 m × 77 cm dbh, respectively; by 2021, only one survived, measuring 30 m x 112 cm.

© John Anderson

Also at Windsor Great Park, another tree planted in 1896 measured 22.86 m × 201 cm in 1978, but apparently has since died. At the Savill Garden in Windsor Great Park, a plant received from Lord Dulverton Batsford Arboretum is doing very well and stands at 9 metres.

© John Anderson

The reserve champion tree is at Beauport Park, Hastings, East Sussex, England. In 1905, the specimen tree was measured at 12.20 m × 32 cm (Mitchell 1996). In 1910 Elwes and Henry recorded it as a young tree, and in 2025 it reached 28 m × 180 cm (Elwes & Henry 1910). It grows on heavy neutral clay. Quercus castaneifolia has been noted to be difficult to grow on heavy chalky soils. At Cambridge University Botanic Gardens, it grows on rich soil of quite high pH. The Batsford tree grows on Cotswold limestone.

© John Anderson

© John Anderson

© John Anderson

At The National Botanic Gardens Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland’s oldest Q. castaneifolia was raised from seed gifted by Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in 1914. By 1932 this specimen was 21 m tall with a trunk diameter of 87 cm! In 2012 it measured 25 m × 111 cm. The foliage is quite broad and the tree is possibly a hybrid. They have a second specimen which was planted in 1932 and is very similar to the Kew specimen and stands at about 20 m. One of the tallest specimens in Ireland is at Mount Usher Gardens, Co. Wicklow, growing on a bank above the River Vartry. It was planted in 1940 and measured 25 m × 133 cm in 2015. In Scotland there are small number of young trees but nothing in the same size as in the southern regions.

Cultivars

© John Anderson

The most well-known cultivar is Quercus castaneifolia ‘Green Spire’, a form with upright branches raised at Hillier Nurseries about 1948. It grows as a tall, vigorous, broadly columnar tree with a compact form. It is recommended for avenue plantings or as a specimen in large open spaces in parks and arboretums. Michael Heathcoat Amory described this tree in 2009 as ‘one of the most dramatic trees in our young collection [Chevithorne Barton, one of the UK’s National Collections],’ growing 16 m in 20 years and dominating the other oaks around it (Heathcoat Amory 2009). The cultivar received the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit in 1993. For a time it was thought to be a hybrid of Q. castaneifolia and Q. libani and this possibility was mentioned in the 1991 edition of The Hilliers Manual (Zale 2018). But the trees at the Sir Harold Hillier Gardens are not hybrids and the suggestion has been removed from later editions.

© John Anderson

Several cultivars were mentioned (as formae) by Aimée Camus in 1936 ('Aspleniifolia', 'Filicifolia', 'Aureovariegata', 'Pyramidalis'), but without descriptions. Their names suggest characteristic foliage or habit, but they do not appear to be in cultivation. Two other cultivars were named for the European park or city where they were selected . ‘Sopron’ was not described, but was listed in a nursery catalogue in 1996, and a plant used to grow under that name at Chevithorne Barton (3.5 m × 4 cm in 2007).

© Roderick Cameron

‘Zuiderpark’ has large, deeply cut leaves to 22 cm long and 8 cm wide. The original tree, planted around 1926 in Zuiderpark, Den Haag, the Netherlands, was 19.6 m × 113 cm in 2021 (Monumental Trees 2025) and a specimen at Arboretum Trompenburg in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, formed a spreading tree about 10 m tall and 10 m across in 2005 (Coombes & Jablonski 2006). ‘Zorgvlied’ was mentioned by Peter Zale in a 2018 article, but with no other information (Zale 2018); it does not appear to be in cultivation.

© John Anderson

Hybrids

Trees of the hybrid between Q. castaneifolia and Q. cerris are found in several collections, and this cross seems to result often from seed obtained from cultivated trees of Q. castaneifolia. Hybrids with Q. libani have also been reported (Coombes and Cameron 2021).

Quercus castaneifolia across the globe

You can find notable specimens in the parks, gardens, and public spaces across mainly Northern Europe. Large specimens grow in Belgium, such as the one at Arboretum Groendaal (34.6 m × 105 cm dbh in 2011) and the Netherlands, e.g. in Helmond, North Brabant (34 m × 156 cm in 2025). Other significant trees are recorded in Germany, France, and Italy. In the USA, it was introduced to Longwood Gardens, Pennsylvania, in 1957, from seed collected in Iran in 1955. A tree of this source had reached 15.5 m × 112 cm in 2016. At Shields Oak Grove in UC Davis, California, trees from seed sent from Kew have produced what appear to be hybrids with Q. cerris. In the Southern Hemisphere, the species is recorded in New Zealand (Hackfalls Arboretum) and Australia (parks in Victoria) and in oak collections in Argentina (Cameron and Coombes 2021, HortFlora 2025).

Cultivation notes

Quercus castaneifolia seems to do best on the fertile loamy to sandy, well-drained soils. This is very much the case in Kew (Kevin Martin pers. comm. 2025), Mount Usher Gardens, and Windsor Great Park. It is happy to grow in open woodland or semi-exposed sites, where it is quick to establish and forms a very stately tree on maturing. The most recent pest affecting the species is the presence of the oak processionary moth (Thaumetopoea processionea), which does appear from time to time in the spring. It has not shown to be of any concern to the tree but is a hazard for the wider public because of the caterpillars’ poisonous hairs, which can cause skin irritation and asthma. Quercus castaneifolia prefers long, warm growing seasons. It is a proven resilient large tree growing on a variety of soils and ideal for future plantings, as climate impacts many parts of the world. This is why it does well in the southern counties of England and in pockets along the east coast of the Republic of Ireland. The preferred clone ‘Green Spire’ has enormous potential for tree avenues and future plantings in urban settings due to its more compact habit.

Acknowledgments

Parisa Panahi and Mehdi Pourhashemi would like to thank the authorities of the Herbarium of Research Institute of Forests and Rangelands and Herbarium of Natural Resources Faculty, Tehran University, for permission to use the herbarium specimens. Thanks are due to Roderick Cameron for his valuable comments and Mostafa Khoshnevis for preparing the information on long-lived individuals of Q. castaneifolia.

John Anderson thanks the following for their assistance: Owen Johnson (Tree Register of Britain & Ireland), Kevin Martin (The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), Amy Byrne (The Morton Arboretum), Prof. Mick Crawley (Silwood Park, Imperial College London - UK National Collection for Quercus), Greg Watson (Chevithorne Barton - UK National Collection for Quercus), and Tony Kirkham (former Head of Collections at The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew).

Editor's note: The 63.3-m-tall tree in Lirasara Forest is likely the tallest oak ever recorded. The previous record holder was a Quercus copeyensis (syn. Q. bumelioides) in Costa Rica, which was measured to be 60.4 m tall in 2017 (see Cameron 2018, p. 186), but it has since lost its top. More details about the Q. castaneifolia in Lirasara Forest will be published in an article by S.E. Sadatinejad and M. Khoshnevis, currently in preparation.

References

Anonymous, 2003. Kimiay-e Sabz. Forest, Range and Watershed Organization of Iran, Tehran, Iran. (In Persian)

Avis-Riordan, K. 2020. 7 amazing facts about Kew’s largest tree. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. [link]

Camus, A., 1936-1938. Les chênes. Monographie du genre Quercus. Encyclopédie économique de sylviculture. Lechevalier, Paris. 1: 557.

Cameron, R. 2018. Brief Encounters with Copey Oak (Quercus copeyensis) in Costa Rica, October 27-30, 2017. International Oaks 29: 181–193. [link]

Coombes, A., and R. Cameron. 2021. 'Quercus castaneifolia' from the website Trees and Shrubs Online. [link]

Coombes, A.J. & E. Jablonski. 2006. Some New and Little-Known Oak Cultivars. International Oaks 17 35–44. [link]

Djavanchir-Khoie, K. 1967. Les chênes de l'Iran. Ph.D. thesis. University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France.

Gorgi Bahri, Y. 1988. Quantitative and qualitative characteristics of Querco-Carpinetum stands in Kheyroodkenar forest (Nowshahr). M.Sc. thesis, University of Tehran, Faculty of Natural Resources, Karadj, Iran. (In Persian)

Habibi, H. 1983. Sole des chênaise du Nord-East de la region Caspienne de l’Iran (Leveh) et leur influence sur la qualité des peuplements. Iranian Journal of Natural Resources 37: 21-34.

Heathcoat Amory, M. 2009. The Oaks of Chevithorne Barton. Adelphi Publishers, London.

HortFlora (Horticultural Flora of South-eastern Australia). 2025. [link]

Karimidoust, A., M. Pourhashemi, S.Z. Mirkazemi, M.K. Maghsoudlou, and M. Alazamani. 2012. Acorn crop estimation of Iran's native oaks using different visual surveys and acorn traps (Golestan province). Technical report No. 5636-12-0, Research Institute of Forests and rangelands, Tehran, Iran. (In Persian)

Maire, R., 1961. Flore de l’Afrique du Nord (Maroc, Algérie, Tunisie, Tripolitaine, Cyrénaïque et Sahara). Editions Paul Lechevalier: Paris. Vol. 7, pp: 117-120.

Marvie-Mohadjer, M.R. 1983. The structure of Iranian oak-forests (Quercus castaneifolia C. A. Mey.) in the eastern part of the Caspian forests. Iranian Journal of Natural Resources 37: 41-56. (In Persian)

Mathieu, A.-A. 1877. Flore forestière. Paris: Berger-Levrault et Cie.

Mitchell, A. 1996. Alan Mitchell's Trees of Britain. Collins.

Mobayen, S., and V. Tregubov. 1970. Guide pour la carte de la vegetation naturelle de l’Iran. Bulletin no. 14, Université de Tehran. Project UNDP/FAO, IRA 7, 20p.

Menitsky G.L. Fagaceae. In: Rechinger, K.H., editor. Flora Iranica. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt; 1971. p. 1-20. (Vol. 77).

Meyer, C.A.V. 1831. Verzeichniss der Pflanzen, welche während der, auf allerhöchsten Befehl, in den Jahren 1829 und 1830 unternommenen Reise im Caucasus und in den Provinzen am westlichen Ufer des Caspischen Meeres gefunden und eingesammelt worden sind. St. Petersburg, Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften. [link]

Monumental Trees. 2025. [link]

Panahi, P. 2011. "Study of the diversity of Iranian oak species using pollen grain morphology and determining their conservation status." PhD thesis, University of Mazandaran, Sari, Iran. (In Persian)

Panahi, P., Z. Jamzad, M.R. Pourmajidian, A. Fallah, and M. Pourhashemi. 2011. A revision of chestnut-leaved oak (Quercus castaneifolia C. A. Mey. Fagaceae) in Hyrcanian Forests of Iran. Caspian Journal of Environment Science 9: 145–158.

Panahi, P., and Z. Jamzad. 2018. Validation of the Quercus (Fagaceae) taxa described by Djavanchir Khoie. Turkish Journal of Botany 42(5): 662– 671.

Panahi, P., and M. Pourhashemi. 2013. Acorn production of adult trees of Chestnut-leaved oak (Quercus castaneifolia C. A. Mey.) in Hyrcanian collection of National Botanical Garden of Iran. Iranian Journal of Plant Research 26(3): 247–256. (In Persian)

Panahi, P., and H. Zare. 2023. Quercus castaneifolia subsp. recurvatus (Fagaceae); a new subspecies from Hyrcanian Forests, North of Iran. Acta Botanica Hungarica 65(1-2): 121–131.

Rix, M., and T.Kirkham. 2009. 640. QUERCUS CASTANEIFOLIA: Fagaceae in Curtis's Botanical Magazine 26:1/2 54–47, 59–63. [link]

Sabeti, H. 1976. Forests, Trees and Shrubs of Iran. Ministry of Agricultural and Natural Resources, Tehran, Iran. (In Persian)

Sagheb Talebi, Kh., T. Sajedi, and M. Pourhashemi. 2014. Forests of Iran: A Treasure from the Past, A Hope for the Future. Springer.

Schwarz, O. 1935. Einige neue Eichen des Mediterrangebiets und Vorderasiens. Notizblatt des Königl. botanischen Gartens und Museums zu Berlin, Bd. 12, Nr. 114, pp. 461–469.

The Tree Register. 2025. [link]

Zale, P. 2018. Insights from a Sole Survivor: Quercus castaneifolia. Arnoldia 75(3): 35–43. [link]